Mapping Movement

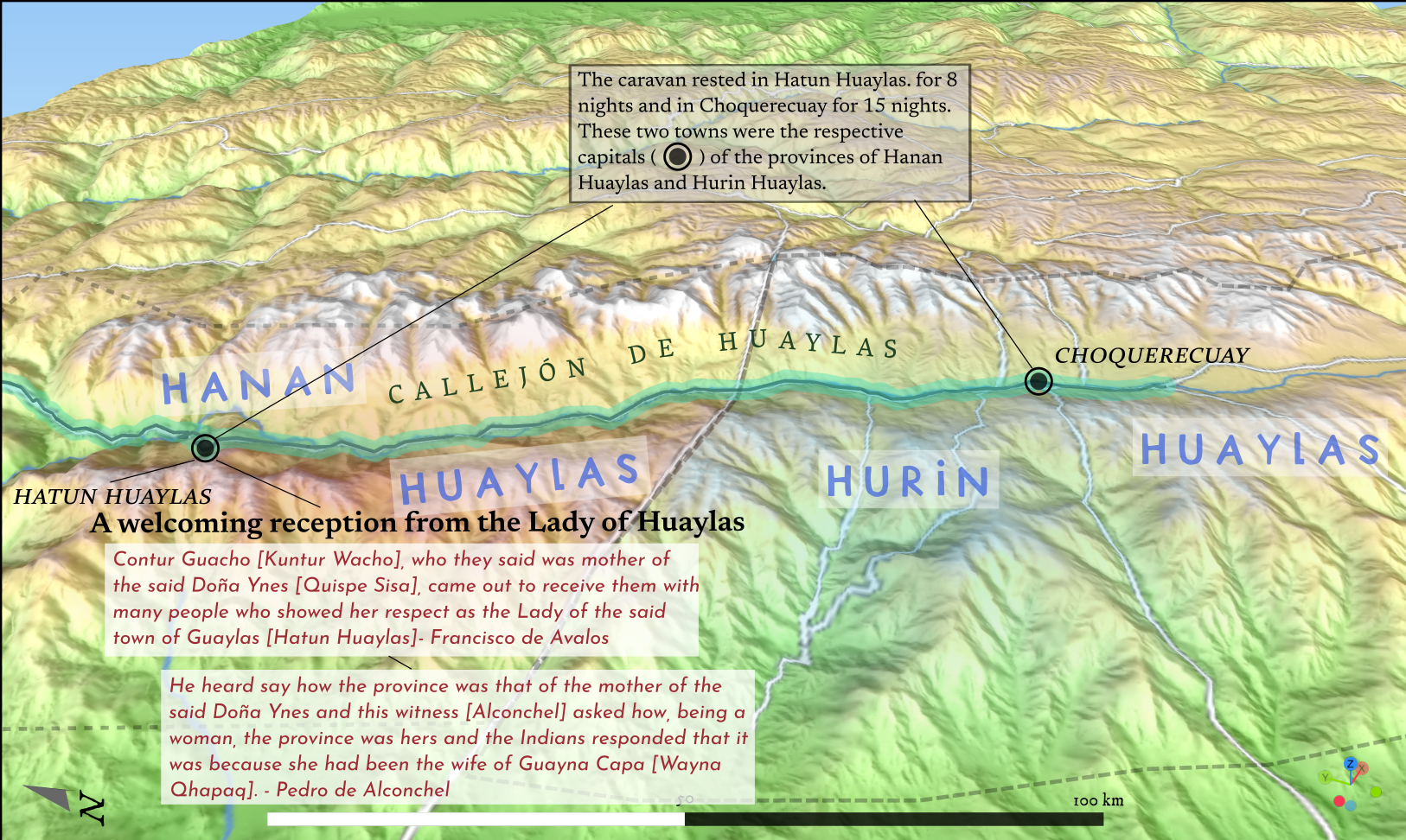

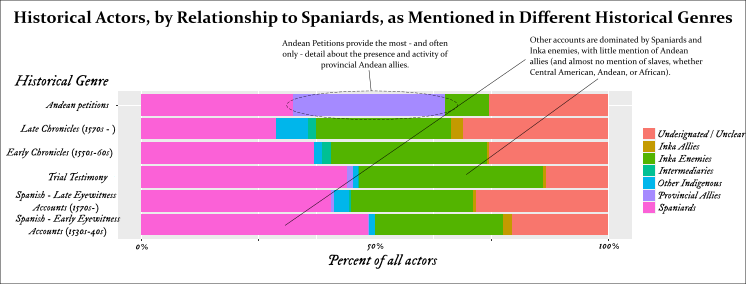

For some time, ethnohistorians have, of course, been mapping the location and territories of Indigenous groups. However, this tendency to map ethnic territory often provides the misleading impression of stasis even when the accompanying text more carefully describes communities under constant flux and historical change.

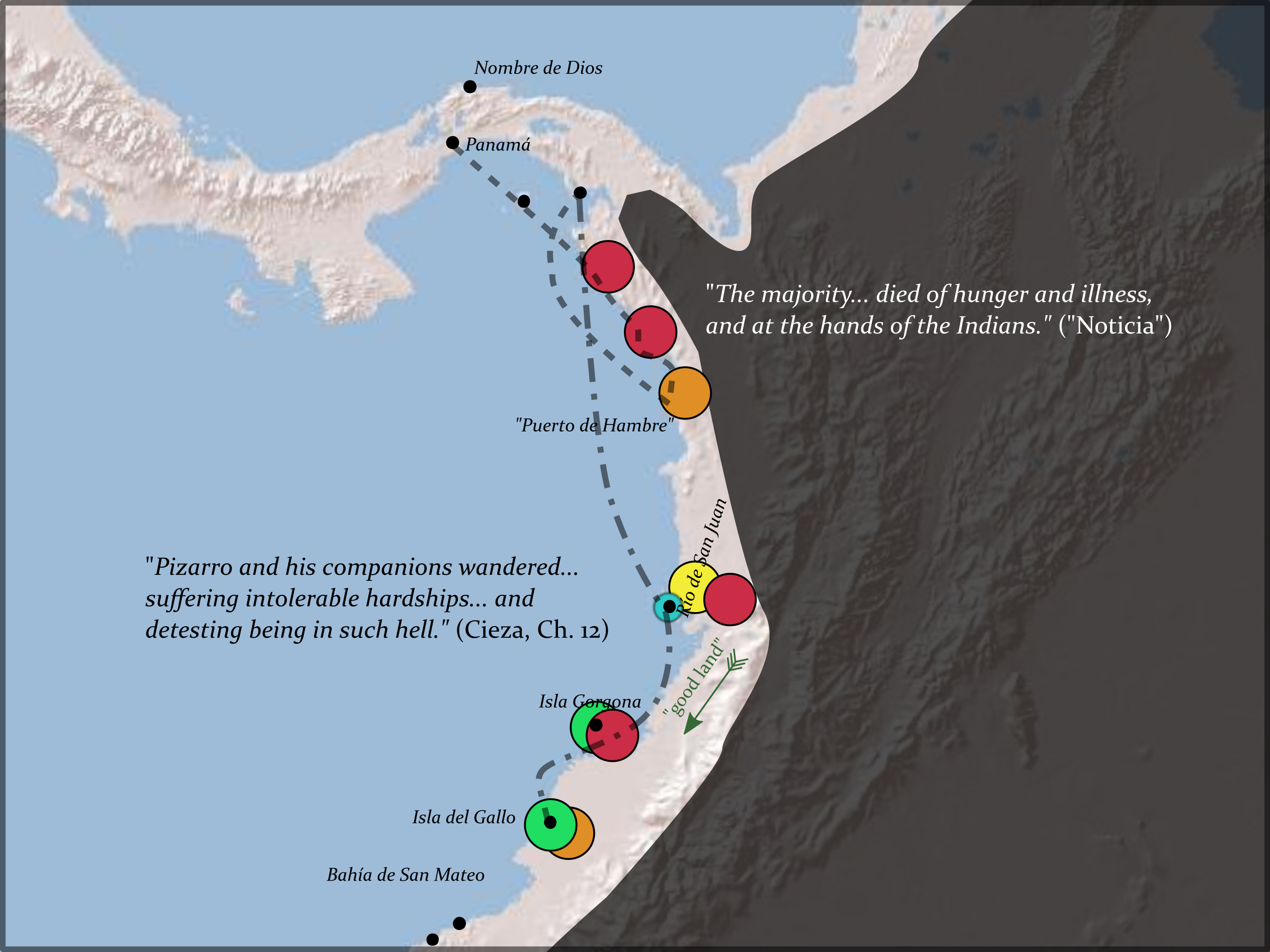

For a history of events, such as the events of the conquest-era, the activity and movement of Indigenous

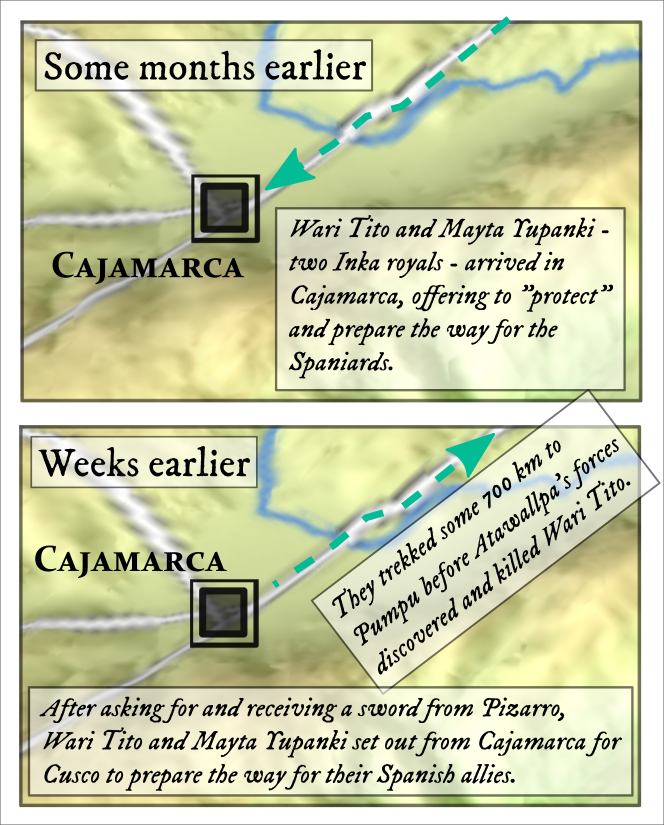

people has remained sorely understudied. In particular, while many scholars have shown how much colonial texts conceal Indigenous agency, there is still a need to systematically reconstruct this activity as a means to uncover the dynamism of Indigenous America during the era of European contact and conquest.

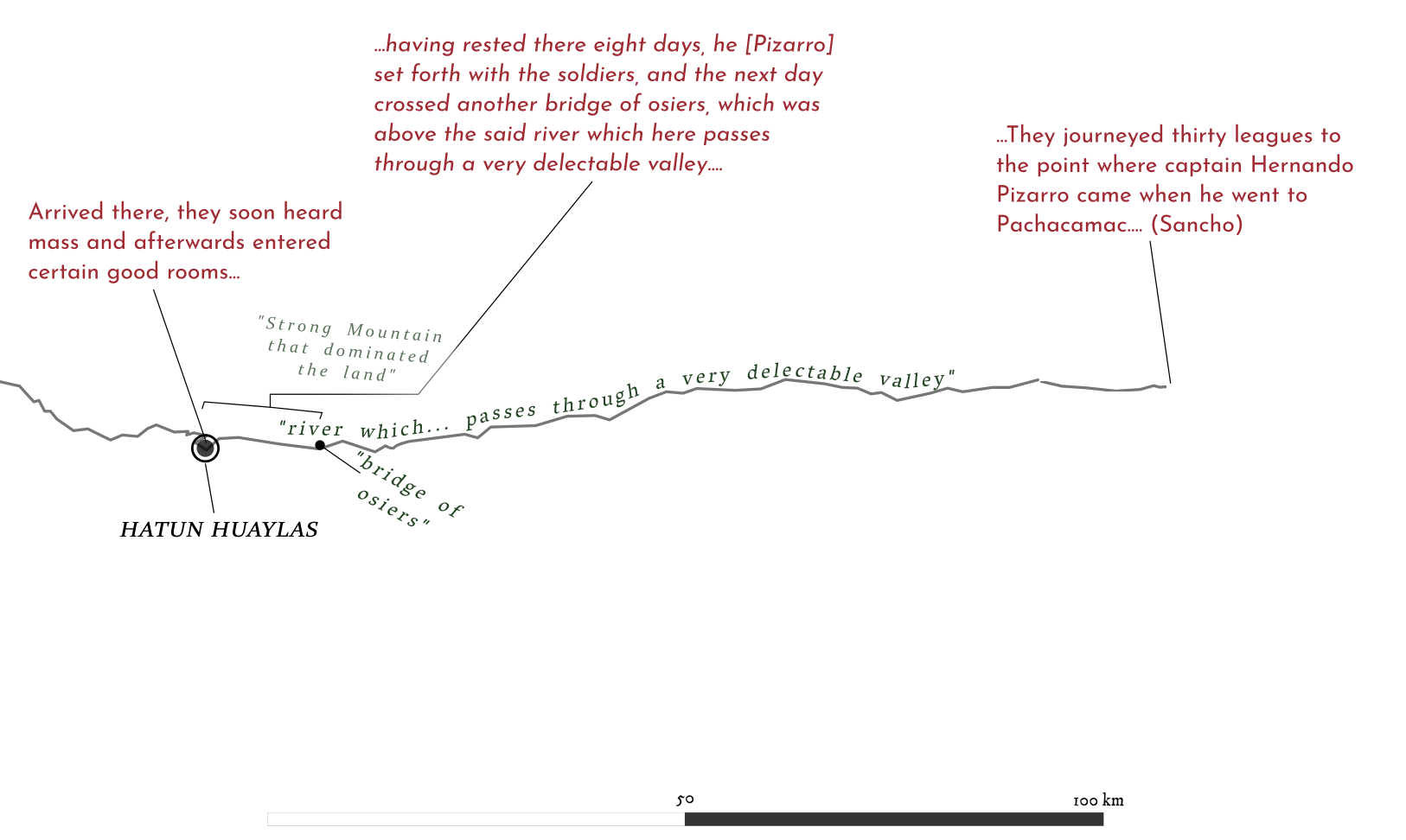

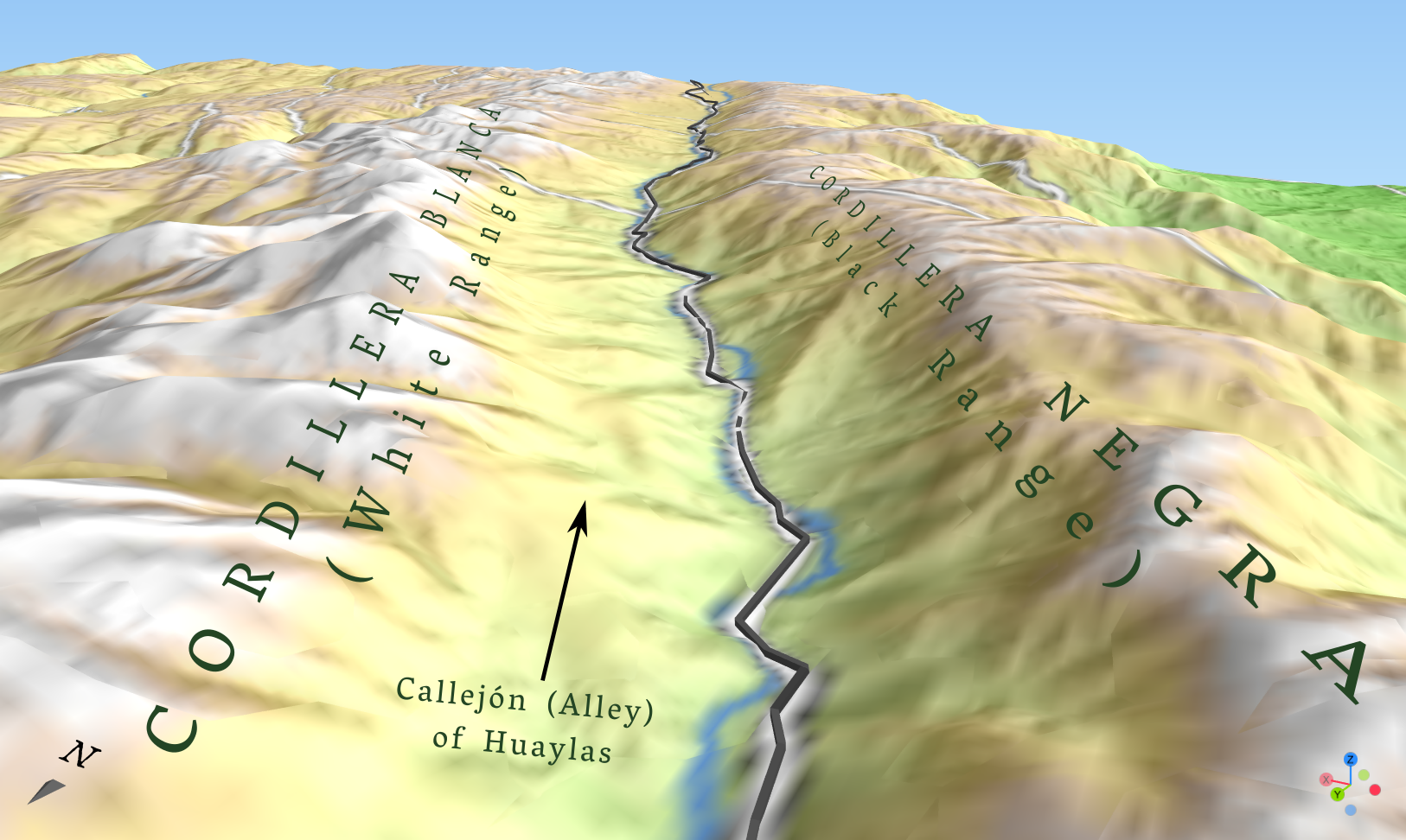

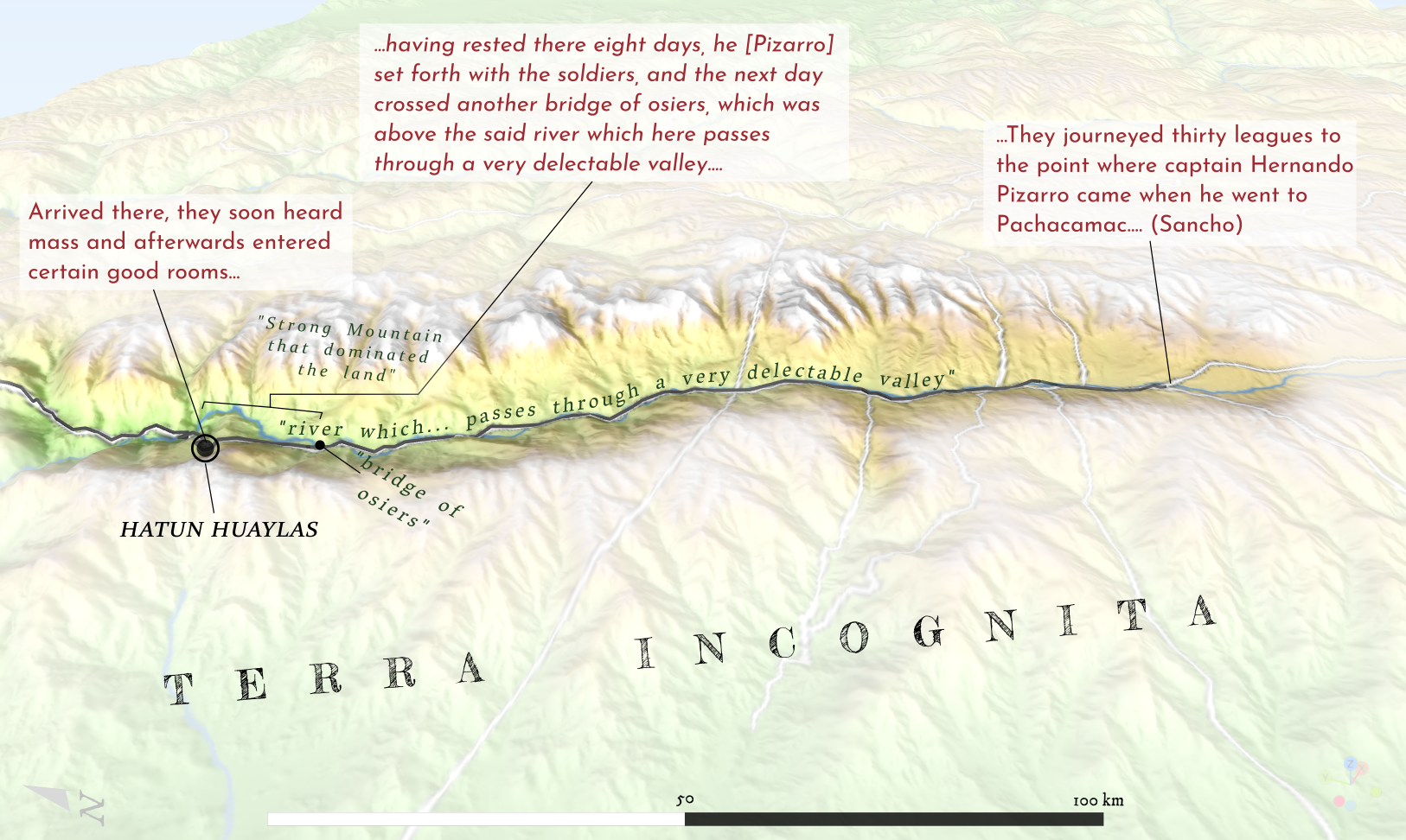

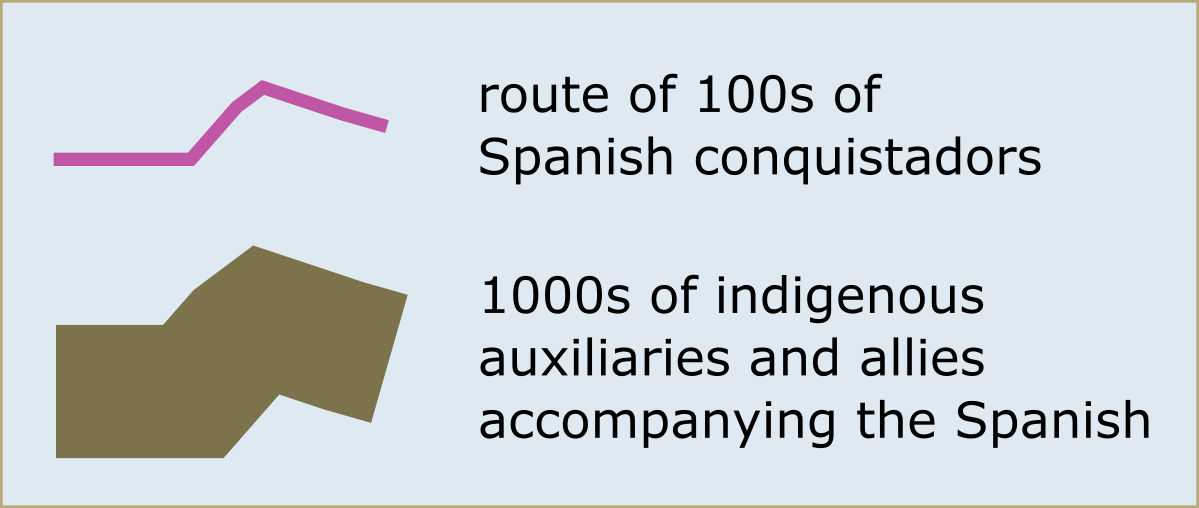

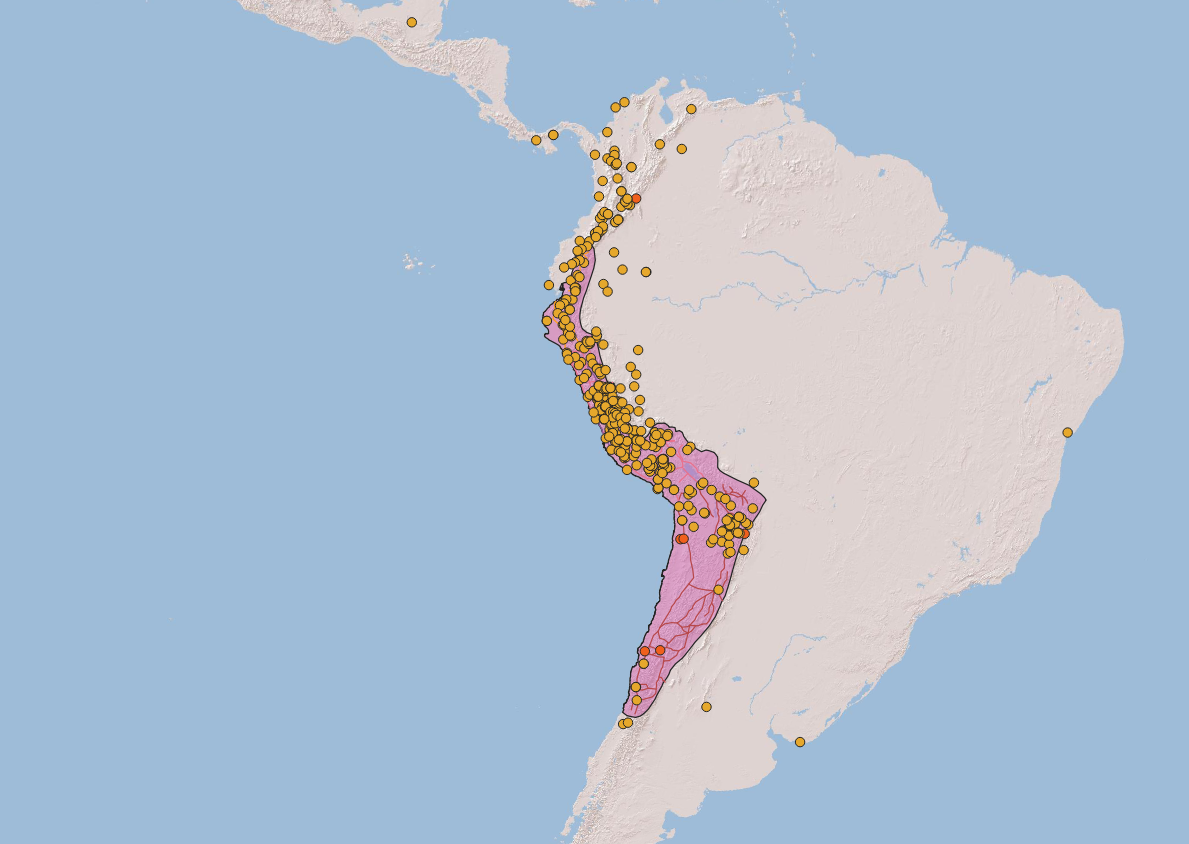

This study moves past European explanations to analyze and map Indigenous activity recorded in European and Indigenous texts. Whereas colonial texts may focus almost entirely on the activity of a few Europeans – only dropping a few hints to the movement and activity of much larger groups of Indigenous people, the maps produced here allow the visual comparison of the magnitude of such activity. Thick lines, representing the marches of Indigenous armies numbering in the tens of thousands, dwarf narrow lines symbolizing the movements of small bands of conquistadors.