Shadowy Figures

Visualizing Marginalized Historical Actors, Events, and Landscapes

Jeremy M. Mikecz

The images presented below accompany my paper for the 2022 Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association and the Conference on Latin American History, to be presented by a colleague of mine (thank you Leo!).

This presentation highlights some of my work from my book in progress, Mapping Conquest. I am finishing up my last chapter now and hope to see it published by next winter. A longer version of this particular paper, "Shadowy Figures," is also under a journal's peer review at the moment.

Thank you so much for reading despite my inability to appear in person at the AHA / CLAH meeting.

Any questions? Please direct them to my email: jeremy.m.mikecz [at] dartmouth [dot] edu.

Contents

I. Shadowy Figures

Creating Humanistic Visualizations: The Invisible Caravan (Cajamarca to Cusco, Aug - Nov 1533)

Inspiration

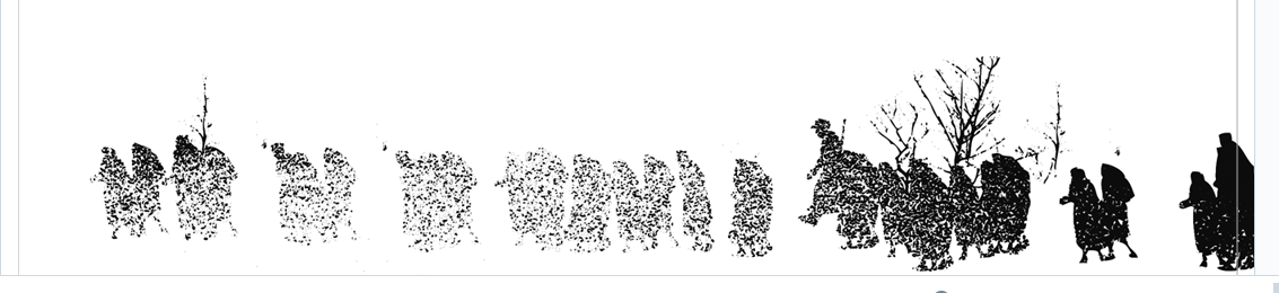

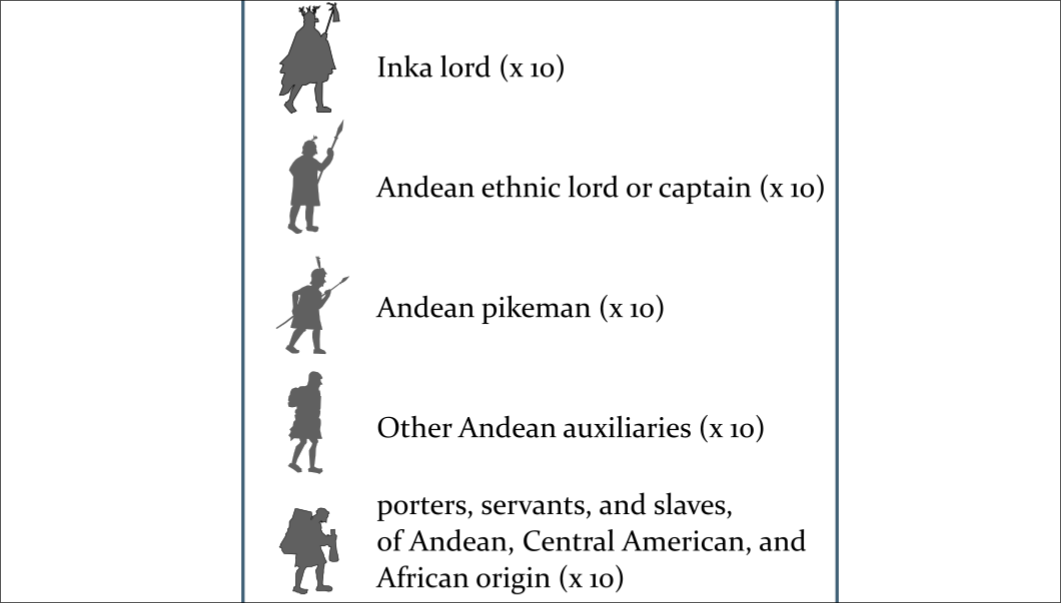

Francisco Pizarro's 1533 march from Cajamarca to the Inka capital of Cusco was a pivotal event in the Spanish invasion and occupation of Peru. However, his advance would have been impossible without the knowledge, labor, and assistance of Indigenous and African people who receive little mention in historical documents.

In reconstructing the stories of these hidden actors, I wanted to know: how can we better represent not just the scope and magnitude of their contributions but also the humanity of history's forgotten figures?

For this project, I found inspiration in a graphic created by Erik Steiner in Knowles, et al. Geographies of the Holocaust (2014).

The Traditional Story

Most contemporary Spanish authors and modern histories - until the last few decades - focused on the 300-500 Spaniards that marched with Francisco Pizarro from Cajamarca to Cusco in 1533. Through visuals we can (literally) decenter the conquistadors and center other actors.

The Invisible Caravan

Click here to view an animated visualization of the Invisible Caravan that accompanied, assisted, and even escorted the Spanish advance. To skip the introductory material and go straight to the visualization, click here (advance through presentation by using right/down arrows on keyboard or swiping right on your phone or tablet).

Note: the full visualization does not currently work on Firefox. Please use Chrome, Safari, or Windows Explorer/Edge instead.

Other Historical Actors

Images for this visualization were created by tracing figures sketched by the Indigenous Andean chronicler, Guaman Poma in the early seventeenth century.

II. Ghost Landscapes

Layers of Historical Landscapes: The Caravan's Passage through the Callejón de Huaylas (Sept. 1533)

Classic histories of the "Spanish Conquest" describe audacious Spanish invasions across the difficult, vertical terrain of the Andes. Modern ethnohistorians have rightly challenged the narrative of Spanish mastery and Indigenous failure. Yet, these new stories have, to an extent, flattened Andean topography and geography, rendering it a non-factor. Reconstructing the dynamic and humanized landscapes of the Andes, encountered by the caravan, helps us look at European narratives anew.

- Mouse over the arrows below to scroll through the images.

- Click on the images to view them in full resolution.

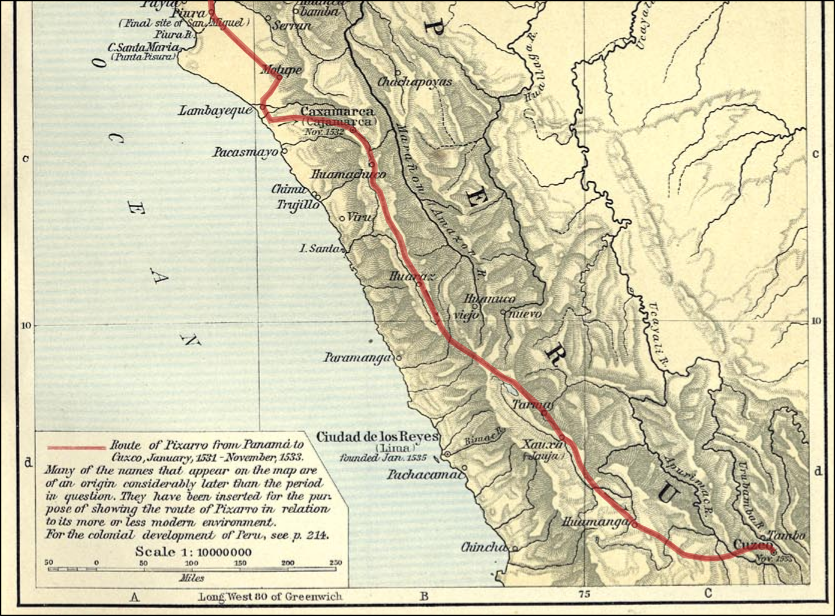

1. A Colonial Map of Invasion

The traditional map of the Spanish invasion commonly found in textbooks. It suggests the relentless, inevitable European advance into parts unknown.

2. Interrogating Historical (and Geographic) Silences

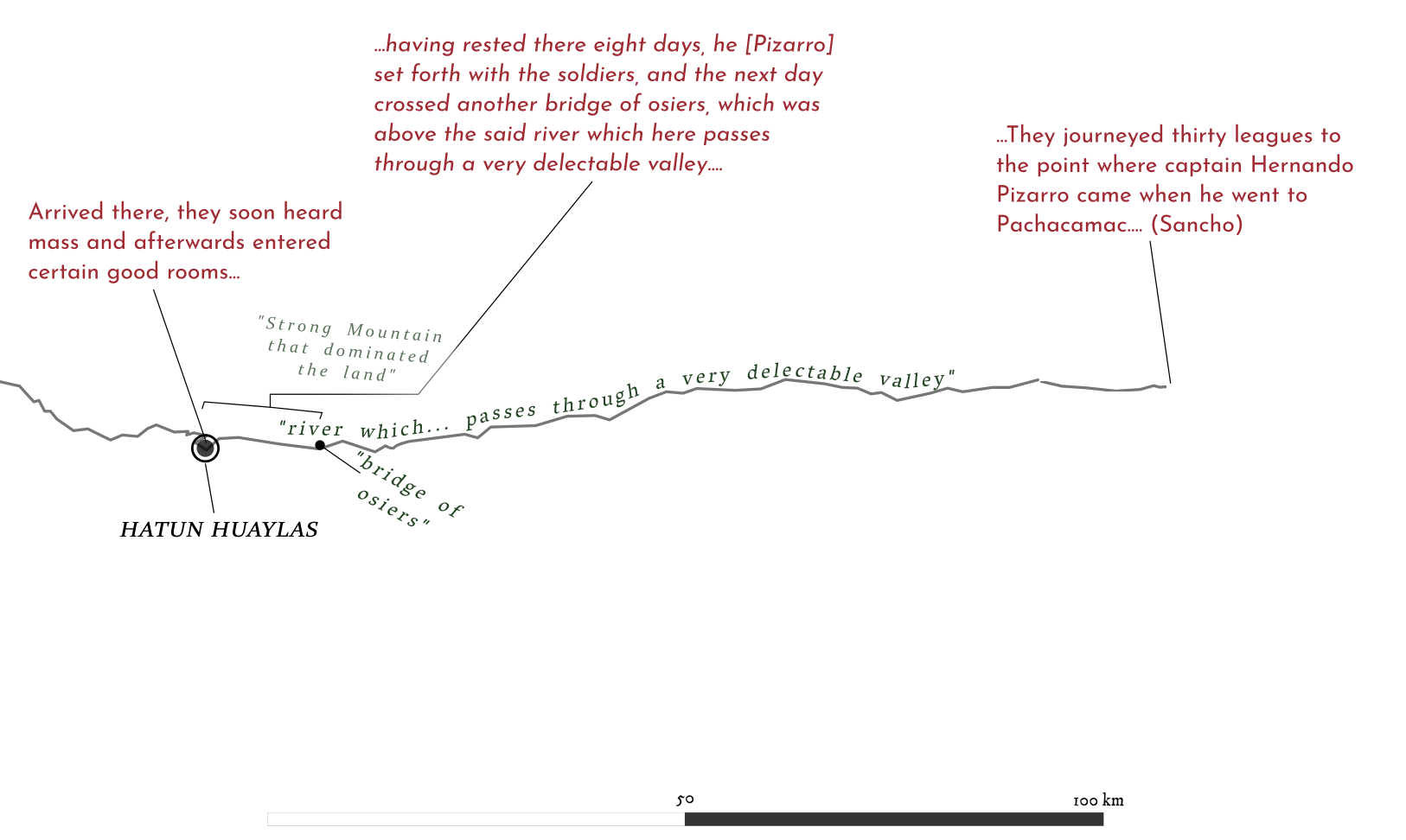

Pedro Sancho, Pizarro's secretary, and the principal chronicler of the 1533 trek to Cusco, had little to say about the conquest caravan's passage through the Callejón (or Alley) of Huaylas

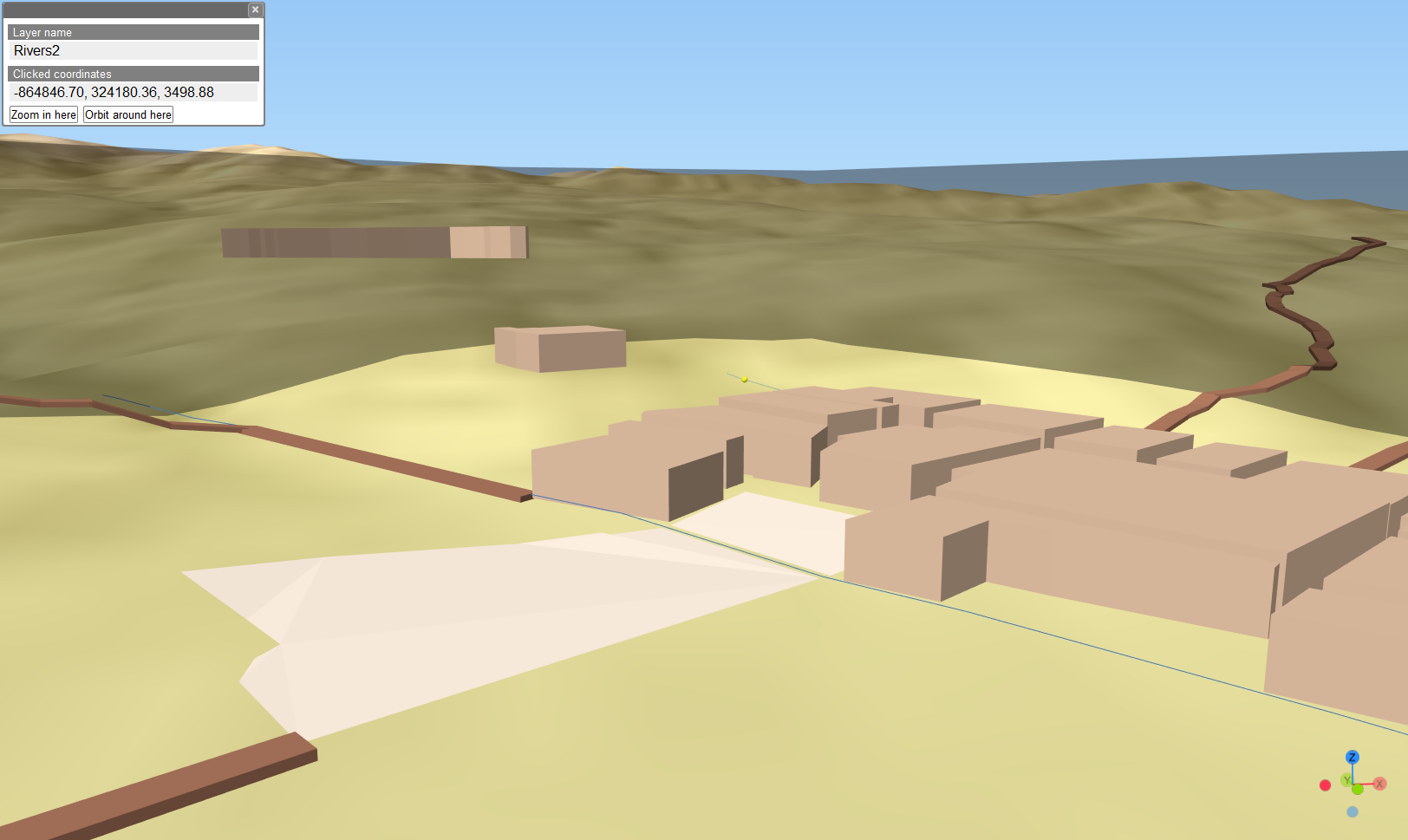

3. (3D) Modeling the Callejón de Huaylas

In Sept. 1533, the multi-ethnic caravan passed through the Callejón de Huaylas. Here I reconstructed the region's remarkable topography, which received almost no mention by eyewitness authors.

4. Mapping Experience and Topography

If we place Sancho's sparse description over the topographic model of the region - even while masking the areas beyond the caravan's sight - we see the extent of the natural and human geography such authors concealed. Why the silence?

5. Silenced Geographies

Charting the words Sancho devoted to different portions of the journey helps explain these silences. He had little to say about the first half of the journey (which included their passage through the Callejón), where they found Indigenous hospitality rather than resistance.

6. Unexplained Delays

Placing a pace chart over this graph shows two other patterns. First, Sancho and other authors offered no explanation whatsoever for some long delays during the first half of the journey. Instead he devoted most of his attention to battles fought during the second half, as the caravan approached the Inka imperial city of Cusco.

7. Local Hospitality

Unpublished trial testimony fills some of the silences from the caravan's extended stays in the Callejón de Huaylas. Witnesses describe the female kuraka Kuntur Wacho and her people welcoming and hosting the caravan during their stay in the region.

8. Negotiating Alliances / Securing Aid

Documents compiled by the Chachapoyas describe their ancestors assisting Pizaro and the caravan until the Callejón, where they then took their leave. As a result, Pizarro and Tupaq Wallpa had to negotiate with provincial leaders to secure additional reinforcements and aid.

III. Re-imagining Historical Events

...from beyond the imperial gaze

The Limits of the Imperial Gaze

The Occupation of Cajamarca and Imprisonment of Atawallpa (Nov. 1532 - July 1533)

The Spaniards' capture of the Inka emperor Atawallpa in November 1532 was an act of dominance. Viewed from a distance, however, they represented a small and vulnerable force that was completely dependent on the assistance of Andean allies. They only occupied 2 towns in all of the Andes in late 1532. In the geographic knowledge map above, dark areas represent the terrae incognitae or unknown lands of the Andes for the invaders. The orbs that fade with distance around San Miguel and Cajamarca represent how Spanish knowledge and understanding dimmed with distance. The fading lines represent fading memory. Only with Indigenous assistance could the foreigners survive in the midst of a vast foreign empire. Only with Indigenous counsel, information, alliances, and an invitation did they dare venture further.

The Invited Invasion

The Forging of Alliances in Cajamarca (1533)

Spanish eyewitnesses emphasize their military victories against the Inka resistance.

Indigenous accounts highlight diplomacy, including the presence of dozens of kurakas in Cajamarca in 1532 and 33, who negotiated alliances with the Spanish invaders as well as with Tupaq Wallpa and other Inkas.

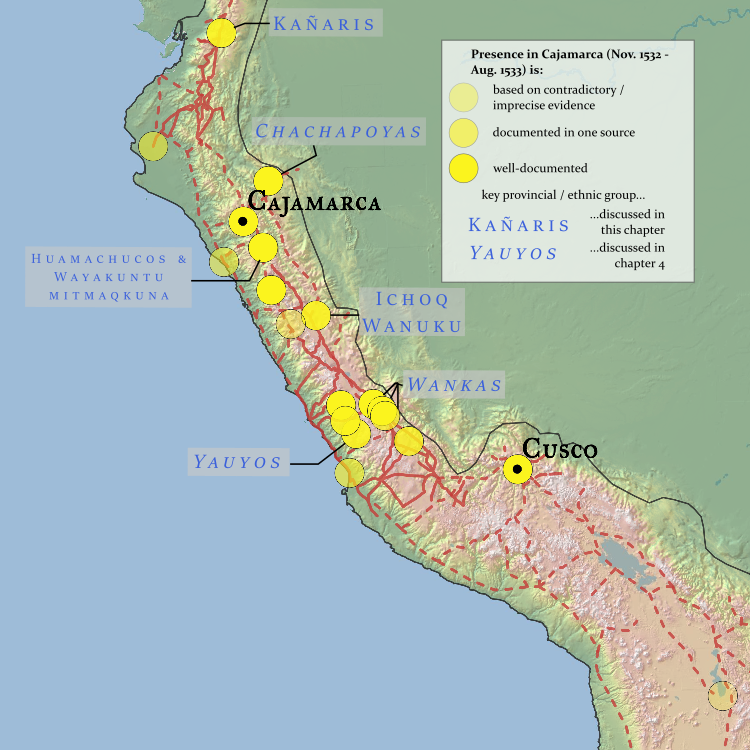

Kurakas in Cajamarca

The homelands of 19 Andean communities documented to have sent representatives to Cajamarca during the Spaniards' nine-month stay there.

Sources: A variety of Indigenous petitions, cacicazgo documents, testimonies, and a few fragmentary references in the chronicles. Many (but not all) of the Native documents have been published by Espinoza Soriano.

Entering Friendly Territory

Thus, when the 300-500 Spaniards - with the caravan of 10,000+ - began their march to Cusco, they were entering friendly territory. Most communities in the central Andes had sided with Waskar during his war with Atawallpa and thus saw Atawallpa's forces as the unwelcome invaders rather than the foreigners.

Sources: Accounts of the Inka Civil War in chronicles by Betanzos, Cabello Balboa, Cieza de León, Murúa, and Sarmiento.

Escort into the Imperial City

The Caravan approaches Cusco (Nov. 1533)

So many historical debates concern the when. However, answering the question of where can often be just as revealing. For example, most Spanish authors indicate that Manqo Inka first greeted Pizarro and the invasion caravan at Jaquijahuana, one day's journey from Cusco. In contrast, Andean accounts describe Manqo appearing on the slopes of Vilcaconga, if not earlier. Why is the location of Manqo's first appearance important? Because the same Indigenous accounts that suggest an earlier appearance describe the Inka appearing with an army, helping to drive off the Quito Inka resistance from Vilcaconga, directing the execution of a hated rival at Jaquijahuana, and escorting the Spaniards and their thousands of companions into the imperial city of Cusco. Spanish authors that suggest a later appearance, in effect, relegate Manqo Inka to the background of these historical events.

Vantage Points

The Siege of Cusco (1536)

Reading Indigenous and other alternative accounts from the conquest era presents contrasting viewpoints of many well-known events.

Visualizing the differences in these narratives sometimes helps interrogate the biases and silences of particular texts. In other cases, however, it offers the opportunity to explore how vastly different one person's experience of an event could be from another's.

Like a Black Cloth Covering the Ground

The Indigenous Horde

A Spanish eyewitness, Pedro Pizarro, described the scene from the perspective of the besieged. "So numerous" were the squadrons of Inka warriors, he wrote, that "by day it appeared that a black cloth covered the ground for half a league around this city." By night, the immense number of campfires in the hills surrounding Cusco illuminated the city like a "very serene sky full of stars." The shouting and general "din of voices" of Inka warriors left the conquistadors "astounded."

A Carefully Orchestrated Attack

A Sophisticated Siege: Barricading the Streets, Flooding the Fields, and Firing Missiles down from above

Other accounts suggest Inka tactics provided their advantage not just numbers. After all, the besieged Spaniards in Cusco were assisted by dozens of Black auxiliaries and thousands of Andean allies throughout.

Titu Kusi Yupanki, Manqo Inka's son, describes a carefully orchestrated attack. Inka captains posted battalions on all four sides of the city. They then began a devastating attack on the city that involved barricading the streets, flooding the fields surrounding the city, and launching flaming missiles (arrows and sling stones) onto the thatch roofs of the city's buildings. This alternative view challenges European accounts lauding their own deeds and lamenting their own pain while obscuring both the humanity and the ingenuity of Native armies, rendering them a faceless horde. It also challenges some modern military historians, who have criticized the Inkas for being slow to adopt effective anti-cavalry tactics.