Mikecz

Transforming texts into databases and maps

Indigenous Knowledge and Early modern databases

The Spanish Empire created a vast 'database' of information about the Americas and its Indigenous peoples. How does the transformation of this record into a digital database allow new insights about the empire and the lands and peoples it claimed?

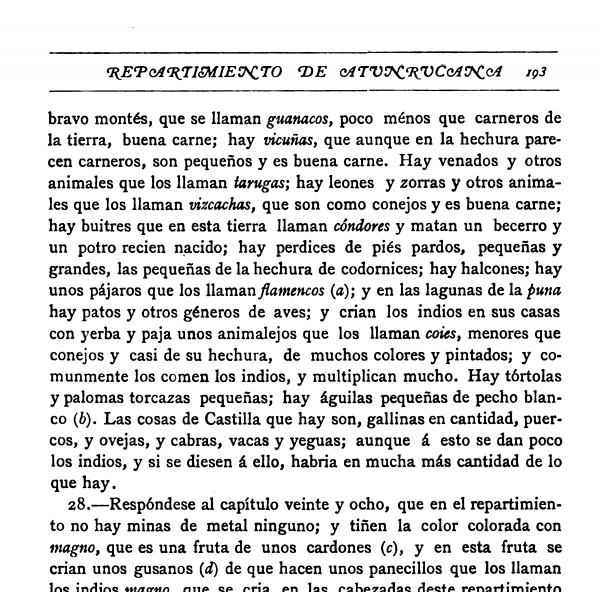

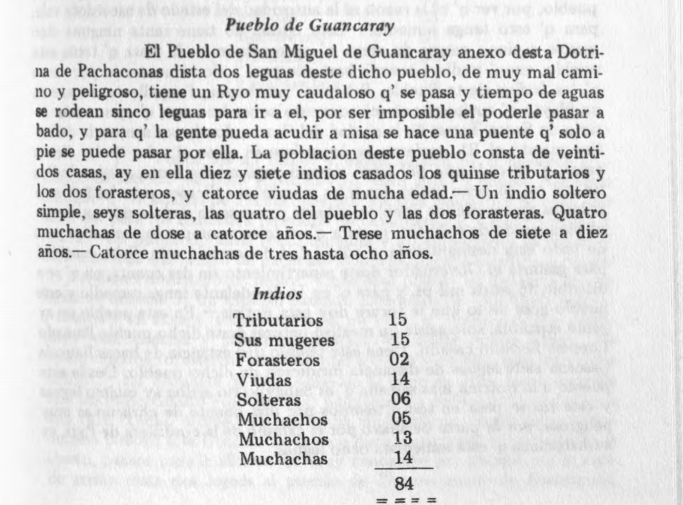

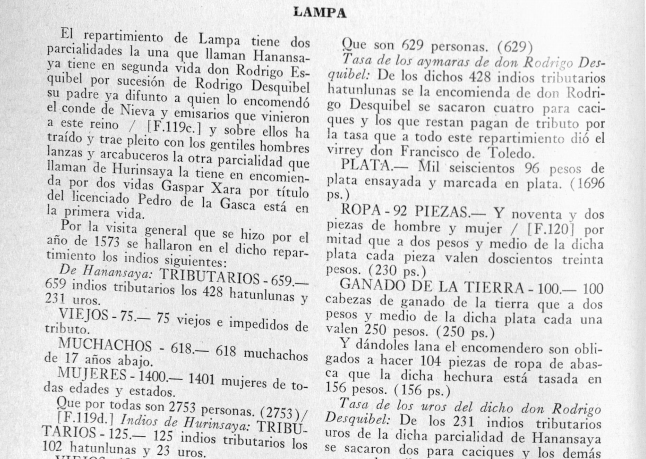

The Spanish Empire's many administrators, bureaucrats, and notaries were prolific record-keepers. They sent administrators, notaries, and interpreters to the realm's many distant provinces to record information about the people, history, economy, and geography of each province. Priests and inspectors performed detailed counts of Indigenous towns' people (including ages and marital status, etc.), their lands (recording property boundaries), and their natural resources (from llama herds to silver and salt mines).

Examples of the census counts, tribute records, and geographic surveys conducted by regional administrators and priests in consultation with local Andean populations

Unlike other early modern empires, this vast paper trail was not just created in a top-down fashion. On one hand, Indigenous people asserted their sovereignty and their own visions of their history and geography while participating in the many bureaucratic surveys of the empire's provinces (like those shown above). On the other hand, the Crown created a decentralized bureaucratic empire that allowed Indigenous communities, African slaves, and people from all strata of society to petition the government, engage in litigation, and, in essence, to negotiate their participation in the imperial project (some key examples below).

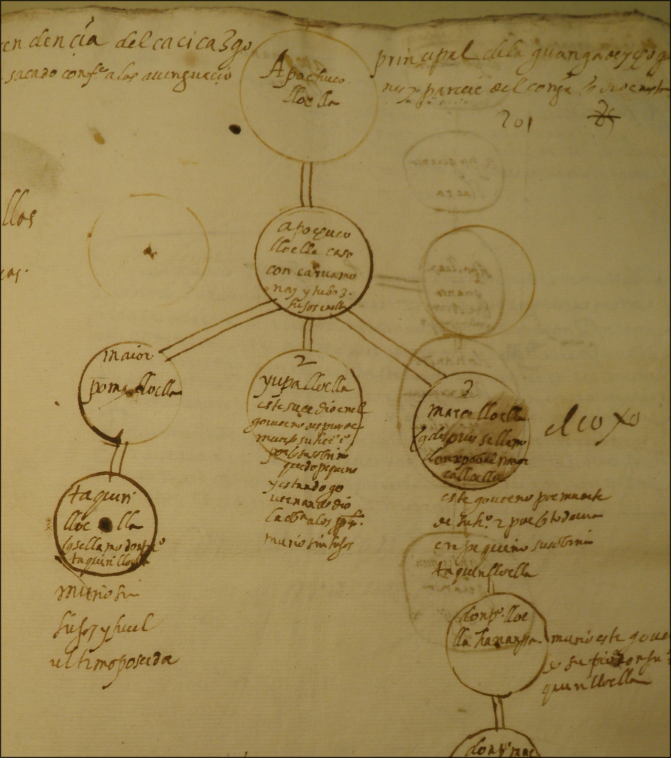

Images of various texts preserving Andean petitions, testimonies, and perspectives. From top left, in clockwise order: 1. a family tree created by a family of regional elites from the province of Ichoq Wanuku and reproduced in a legal dispute over heritary rights to rule the province (a cacicazgo case) in 1606. The man at the top of the tree is Apo Chuqui Lloclla, who his descendants said administered the province during the reign of the Inka ruler Tupaq Inka Yupanqui (ca. 1473 - 1493). 2. A painting of a noble father, with his two sons, who in the late sixteenth century governed an autonomous chiefdom of Afro-Indigenous people in what is now coastal Ecuador. 3. The coat of arms awarded by the Spanish Crown to the provincial Wanka lord Guacra Páucar in recognition of the service he provided to Spain during the conquest-era (note the three severed Andean heads in the top left). 4. The first of two images by the Andean author and artist Guaman Poma. He shows the military assistance provided by Andean allies during the conquest-era. 5. Town council (cabildo) records from the province of Chachapoyas in 1548 (from the British Library). 6. Land records from the town of Cachora, near the Apurímac River, in 1596 (Archivo Regional de Apurímac). 7. Here, Guaman Poma depicts the reading of the Andean knotted cord recods (khipus) in a historical chronicle published by the priest Martín de Murúa (from a facsimile copy available at USC's Special Collections Library). 8. A published copy of the testimony of Inka nobles about the lands conquered by Tupaq Inka Yupanki. 9 (center). Title page to a fascinating but controversial set of documents preserved in the Archivo Regional del Cuzco that were compiled in a lawsuit in the late 1700s and represent over 300 years of Inka and Andean history.

The challenge lies in analyzing those documents that have since been published in more systematic ways while still incorporating unpublished and non-textual evidence. Unpublished records disproportionally include documents written by Indigenous authors or recorded at the local level.

How can digital text analysis transform historians' study and understanding of the past?

The problem of scale

Many social scientists compile data, construct large datasets, and then share this data with other scholars.

Some literary scholars engage in 'distant reading', creating large corpora of digitized texts.

Historians - especially pre-modern historians - rarely work with larger digitized datasets or text corpora. There are good reasons for this: the labor required to compile such datasets, the fact that many of our historical sources are not published, and the difficulty in digitizing the ones that are.

Nonetheless, I believe there is a middle way for historians: a compromise between distant and close reading and between macro- and microanalysis.

Towards a medium reading and meso-analysis

Distant reading often involves the mining of 1000s of texts for patterns.

Historians often work at different scales. They may closely read and re-read a few key texts while also skimming thousands of other documents looking for a keyword here or a clue there.

My construction and analysis of this digital text corpus involves a mixture of both approaches. My corpus includes many of the most important historical texts for study of the sixteenth and seventeenth-century Andes. As a corpus that will ultimately include about 200 volumes or approximately 50,000 pages, it is too large for a careful close reading but small enough to allow some manual editing.

Borrowing approaches from close and distant reading / macro and micro-analysis, a meso-analysis of this corpus involves:

- The manual checking of OCR'd texts of poorer quality, while programmatically correcting common errors in higher-quality scans. Conversely, scholars mining large corpora often have to tolerate OCR'd texts with frequent errors.

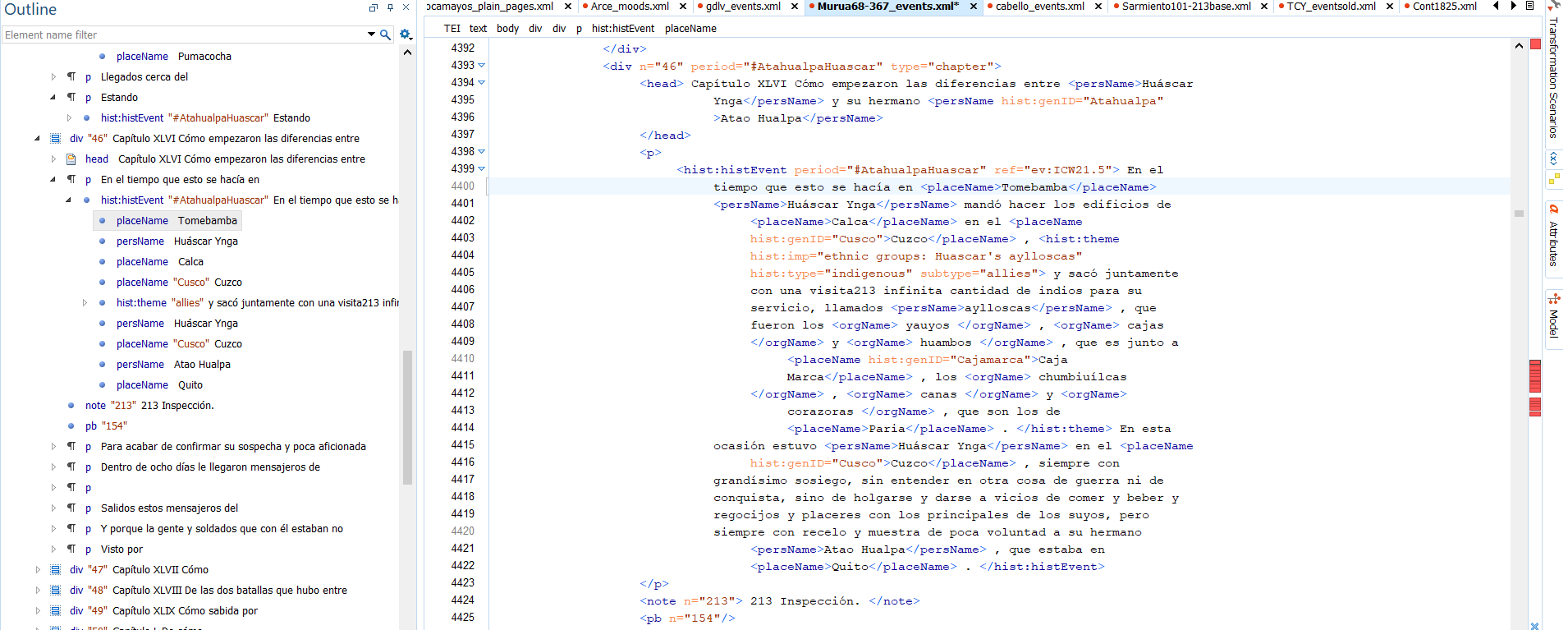

- Structuring texts using a semi-automated approach. Using Python, I write programs that automatically encode structure (chapters, pagebreaks, paragraphs, footnotes, etc.) in xml/TEI. I then manually check for errors and re-run the program until I have 100% accuracy. In contrast, large-corpus text-mining techniques often rely on the analysis of "raw" or unstructured texts that make targeted queries and searches more difficult..

- Encoding content information with a semi-automated approach. This involves automatically identifying named entities - names of places, people, and organizations - and other basic content information (like dates). On old Spanish documents the accuracy rate of named entity recognition (NER) is often fairly poor: ~50 or 60%. I then export frequency lists of tagged entities to check for recurring errors (i.e. the incorrect tagging of "Cusco" as a person name 110 times can be fixed in one step). In this way, I iterate back and forth between summary tables and the texts until I achieve 80 or 90% accuracy. Researchers working with large numbers of texts often have to spend significant time training NER and other natural language processing tools on hand-encoded training data. This helps increase the accuracy of NER but is a time-consuming process.

- Performing complex and targeted queries of this encoded dataset. The searches and queries one can perform on raw texts is far more limited.

Imbalances in the Historical Record

For a long time, documents published from early colonial Perú privileged the perspectives of higher-level Spaniards. In the twentieth century, however, ethnohistorians began publishing many more documents written by or recorded with the consultation of Andean communities.

There still remains an imbalance in the published historical record that favors Spanish colonial officials and some key Inka elites over common Spanish settlers, people of African descent, and Andean communities. Rectifying this archival imbalance requires adopting an iterative approach that moves back and forth between distant and close reading as well as between published (and digitized) documents and unpublished texts. Visualizing the structure and gaps of individual archives and document collections becomes paramount.

The problem of reproducibility

Social scientists commonly create and share datasets that allow their research to be tested and reproduced by others. By making these datasets publicly available, they also allow scholars to use the same data to answer different questions

Historians, however, commonly have to start their work from scratch. This project seeks to conceptualize and demonstrate how a searchable and visualizable text corpus serves not as a replacement for traditional research but as a complement.

Exploratory Data Analysis and Pattern Discovery

Applying data visualization to uncover hidden patterns. In my research, I use data visualization techniques to identify and examine patterns found within texts and to identify and explain gaps and silences within these texts. In this way, data visualization allows the interrogation of historical texts and the ways certain stories are privileged while others are marginalized or erased altogether.

The creation of the Early Colonial Andes corpus allows a variety of studies answering historical questions, both old and new. A few studies I am working on include:

Indigenous Geographies: Mapping and Decoding Andean Spatial Information encoded in Historical Texts

Only a few maps from the sixteenth and seventeenth-century Andes survive today. Nearly all spatial and geographic information from this period were recorded in texts.

This project is the first effort to decode this spatial enformation encoded in these texts for centuries. It begins with some simple but still unanswered questions. Who lived where? How did information and power travel across Andean mountain passes and vast distances? Where were the refuges and zones of escape and resistance to Spanish colonial power? How did the Spanish colonial project alter Andeans' environments and their relation with the land?

The Databases of a Bureaucratic Empire: An Early Modern Information Revolution

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Europe experienced multiple monumental historical events that created an information revolution that ended the Middle Ages and inaugurated the modern age. Europe experienced the invention of the printing press, the discovery of the Americas, and a broader cultural phenomenon that included the spread of humanism, the rise of literacy, and the Reformation. Various other information revolutions followed, including the publishing revolution of the nineteenth century and the current dawn of the digital age.

A study of the ECA corpus permits a comparison of these three historical moments. Many of the sources included in this corpus were written in the first, rediscovered and printed in the second, and now stand to benefit from being digitized in the third.

Moreover, the ECA corpus brings the dark sides of the onset of the global age into the conversation: conquest, colonialism, and exploitation.

The Corpus

The Early Colonial Andes digital text corpus

| genre / type | key examples | approx. number of volumes |

|---|---|---|

| Imperial Surveys and Censuses of Indigenous Lands, Provinces, and Peoples |

|

10-20 volumes |

| Historical Chronicles |

Chronicles of pre-contact and post-contact history

|

~30 volumes |

| Document Anthologies and Collections |

|

100+ volumes |

| Summary Information of cosmographers |

|

5-10 volumes |

| Traveler documents |

|

~10 volumes |

| Town Council Records | libros del cabildo de:

|

~10 volumes |